As we say, สุขสันต์วันสงกรานต์. Mid-April is the Thai New Year festival week. There will be no water fights where I currently am in Brooklyn. Here, the weather’s only getting warm enough to start to expect fire hydrants spraying out at block parties. For me, the rebirth rites of spring is a good time as any to maybe start a newsletter.

If you’re receiving this, you’ve signed up for something from me on another platform or I’ve unjustifiably signed you up. I don’t intend for this newsletter to be more than very occasional. It’s another way to commune with readers as I continue work on larger projects—likely a little longer than my usual IG posts. Feel free to do with my communications as you wish.

Writing as Bonsaiing

When I was in Bangkok recently, I got into bonsai. I’ve enjoyed helping out my parents with their garden but kept no plants of my own. A bonsai, I thought, would be small enough to place in an inconspicuous corner: my infinitesimal contribution of oxygen to counter the city’s dusty air, as well as an additional fulfilment of requisites in a middle-aged Asian man’s life arc.

I bought a young premna and planted it in a carved rock from the garden. That was my gateway bonsai. I’ve since added a chaste tree, a Singapore holly, a button bush, and a couple of others. My corner expanded into a good two meters of space on a wall ledge.

If and when I have my own adequate outdoor space, I imagine I’ll try tamarind, bodhi, maybe even mango bonsai. For now, I’m happy with my group of small, inexpensive proto-bonsai—my trainer plants to get better at keeping and shaping them. They’re also a series of exercises in attention, time, and chaos—not so different from how I write.

Like all beginners, I started with the basics. I’ve based the potential shapes of most trees on the sacred “triangle” and classical branching patterns. There’s branch 1 at the bottom, before you alternate on the other side to branch 2, and you look for a third branch to jut somewhere out the back, before choosing the direction you want the main trunk to grow and again start your next series. Each tree has a natural shape you think might work well. You cut off the branches you don’t need, trim off messy leaves, and twist wires for brute, sustained re-shaping.

With my current trees, I’m letting the Chinese privet pretty much grow freely until it gets larger and trimming the calamansi into the shape of a trident, just because. I’ve even tried attaching the roots of a Barbados cherry to a rock with natural fibers and covering that with soil. Will that work, instead of using the recommended plastic ribbons? I’m not sure. All I can really do is hope for the best. The little trees will take the shape they want, and I either accept or resist it. Only time will show me what that ultimate shape might be.

Bonsai is an artificial natural, like the way our written stories—forced out of their ideal plane to compromised realization—are artifices of our natural imagination. A tree in a small pot. Lives told through words in a little book.

In writing, I also try to let my narratives grow into their own, before I return to them and see how they might be reshaped. With my novel BANGKOK WAKES TO RAIN, intention and early visions certainly changed over time. I didn’t quite know which characters would find their arcs extended. I had no idea when I started that a good part of the book would concern a future time for the city. It all started with something of a seedling: the moving image of a Thai woman sweeping outside her restaurant in Japan. Then a branch grew: a Thai boy looking through his father’s books in mid-century London; then another: a frustrated American missionary treating patients in 19th-century Siam; and another: an African-American jazz pianist performing on the stages of neon-lit places I rode past as a kid in Bangkok.

Those narrative branches sometimes grew off-shoots of their own. Sometimes they didn’t. I could only find out by letting them grow out, before I intervened, clarifying characters by trimming overgrowth and twisting time as I might with wires to eventually form the novel’s overall early shape. Decisions shape the story as it grows. If it doesn’t work out, I might cut and see how the branches might grow back.

It takes time. We live under capitalistic expectations that demand the quickest path to the exploitation of anything of potential value—with the ecstatic fantasy of production being one without time. Art is entering a new age of instantaneous commodification. The grand promise of the latest technologies is that one can create without creating—a simultaneity of demand satiation and supply provision happens with the tap of a key.

But the technocratic mind forgets or perhaps has never known, that without time, there is no life. Life is a story—from seedling to tree to shapes that emerge, over time. It’s the uneasy and uncertain succession of decisions—what one might even call conscious agency—that makes life and art. Making them within a story is what keeps me writing, and hopefully it’s what will keep folks reading.

I’m keeping that in mind as I work on my current larger project: a partially realized novel I’d set aside a few years ago. I dug it out and took another look recently, after becoming frustrated with a different endeavor. Turns out the roots had attached to the rock. I could see new branches growing from the old and where they might want to go. Neglect has done its deeds. Time and attention, I hope, will keep showing me how.

Anyway, here’s a look at the first 1/3 of that project draft, all printed out for me to very roughly edit by hand, and then it’s on to either the next or last third.

The IPCC: Our Time to Act Is Now

Since my university days as an environmental science and policy student, I’ve been reading reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. As a young person then, I trusted that much would be done to veer us from the path towards ecological self-destruction. It turns out that our society’s sense of self-preservation couldn’t overcome our ongoing obsession with perpetual economic growth at all costs.

When I was writing the more futuristic parts of BWTR, I often referred to the IPCC reports to see if my imagination of what might happen in Bangkok could be overblown. Any future-looking forecast in IPCC reports tended to be, inherent to the nature of science as subjected to politics and appearances, on the conservative side, with careful wording to avoid any hint of alarmism even as alarm bells were sounding louder with each report. The sequential turns of horror lay within each update of how much worse the worst was looking to be. We kept exceeding many measures we shouldn’t, and we did very little to curtail our excesses.

When the sixth report came out last year, it was a terrifying read—and also a very long, technical one that I wouldn’t think of attempting in full. Thankfully, in March the IPCC released their synthesis report, which acts as a summary of the full report and outline actions we can actually take (tldr; end the fossil fuels industry and cease destructive agriculture).

Look, we all know we’ve gone past certain thresholds—our earth will warm up and we and every ecosystem will suffer for it—but it doesn’t mean that we should let fossil fuel and other emissions-spewing industries unleash climate catastrophe in its fullest, most hellish realization on us and future generations—human and beyond.

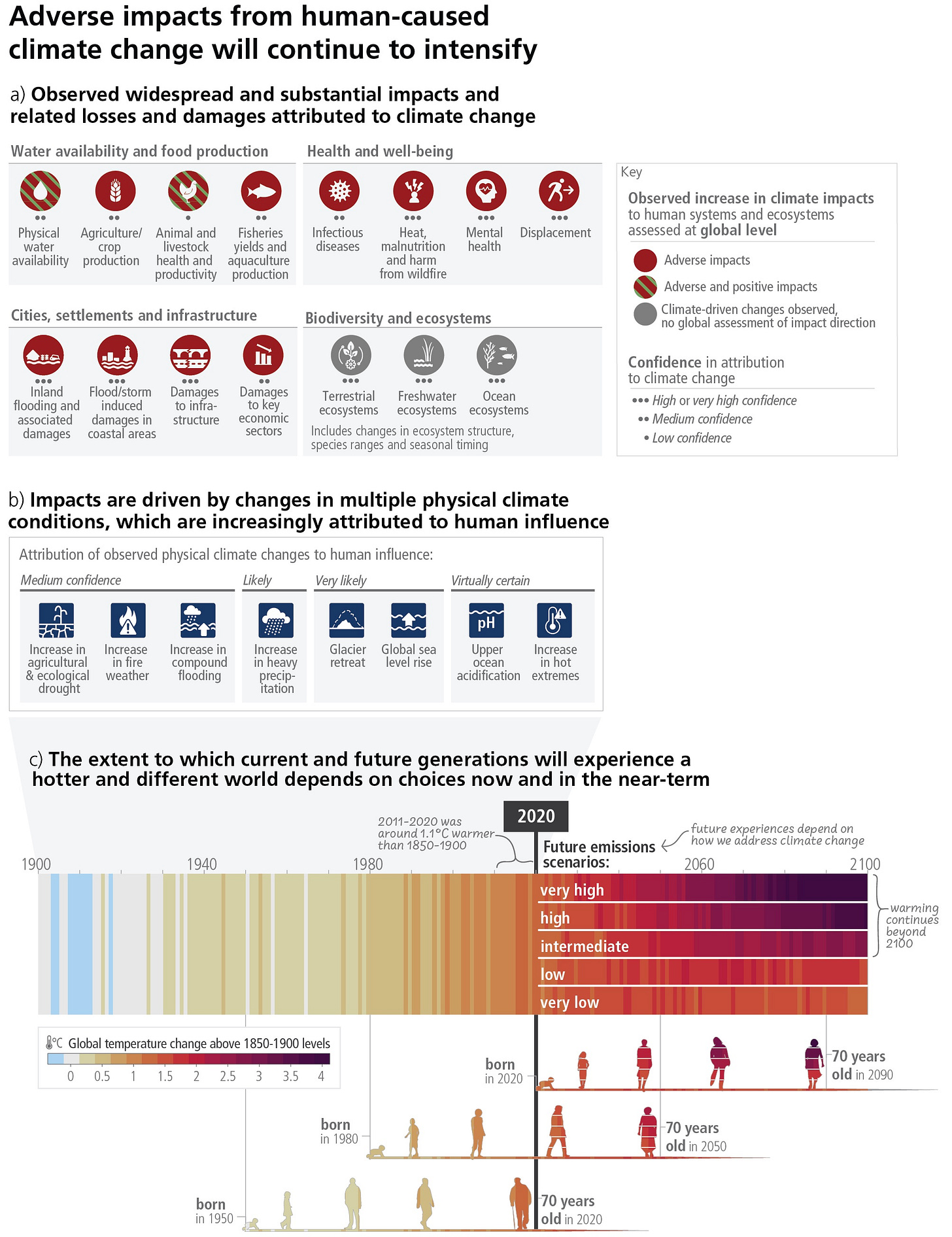

If you think that you won’t experience it in your lifetime, take a look at this chart from the synthesis report and think again. There’s much for us to do ahead. We can prevent the worst from happening.

What I’m Reading: Philosophers

I read mostly fiction, but most recently, I’ve been picking up tomes by philosophers (what greatness lurks in the $1 carts outside used bookstores). I’m only marginally familiar with most; I’m essentially catching up with more erudite friends and readers. Some are re-reads, like Sartre’s NAUSEA, perused with great emotive resonance but the mildest comprehension at East Village cafes that are no more, and Marcuse’s The ONE-DIMENSIONAL MAN, recommended to me by an anarchist friend in my more youthful years when I went to things like friendly anarchist potlucks in a Starbucks and Whole Foods-free Williamsburg. Others are newer, strange works that I look forward to attempt to understand for the first time.

These aren’t casual reads, but they’re also not incomprehensible. In fact, I welcome the pleasure of confusion. The ecstasy of the amateur comes through the discovery of unknowns. Once I realized that mastery is a doomed as a conscious goal, many delusions disappear.

I’d recently talked to a few friends about the notion of the imposter syndrome, and how it’s perceived as a bad thing because our ego is usually wrapped up in its self-belief about competence. We’re made to become too anxious over our value in society and trapped by the survivalist compulsion to display mastery, to the degree that we forget there’s delight to be found in confronting the uncertainty of our knowledge.

Why should we expect ourselves to be authentically masterful with anything? Because some institutional certification claims we are? Because we’ve been well received and recognized for something we’ve created in the ever-distancing past? To me, mastery seems like a sepulchral attainment. It offers little but a finality of stasis.

Let’s all be imposters. For me, to not be an imposter is to be tediously bored.

For now, I’m very much enjoying my philosophical amateurism. I can digest anything and interpret and misinterpret it as much as I’d like. So I randomly open up to a page in the Adorno and let my eyes drop on a few lines. He writes: “Man’s life becomes a moment, not by suspending duration but by lapsing into nothingness, waking to its futility of the bad eternity of time itself. In the clock’s over-loud ticking, we hear the mockery of light years for the span of our existence.”

What does that even mean? OK, I think I can guess what Adorno meant to say, after taking in the entire section, but do I really understand this? It doesn’t matter. Reading in-itself turns into reading-for-itself. I love it.